In August 1921, author A.A. Milne bought his one year old son, Christopher Robin, a teddy bear. This did not, perhaps, seem all that momentous at the time either for literary history or for large media conglomerate companies that used a mouse and a fairy as corporate logos. But a few years later, Milne found himself telling stories about his son and the teddy bear, now called “Winnie-the-Pooh,” or, on some pages, “Winnie-ther-Pooh.” Gradually, these turned into stories that Milne was able to sell to Punch Magazine.

Milne was already a critically acclaimed, successful novelist and playwright before he began writing the Pooh stories. He was a frequent contributor to the popular, influential magazine Punch, which helped put him in contact with two more authors who would later be associated with Disney animated films, J.M. Barrie and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In 1914, he joined the British Army. In what is not, unfortunately, as much of a coincidence as it may seem, he was wounded in the Battle of the Somme, the same battle that left J.R.R. Tolkien invalided. The experience traumatized Milne for the rest of his life, and turned him into an ardent pacifist, an attitude only slightly softened during Britain’s later war with Nazi Germany. It also left him, like Tolkien, with a distinct fondness for retreating into fantasy worlds of his own creation.

Buy the Book

Winnie the Pooh

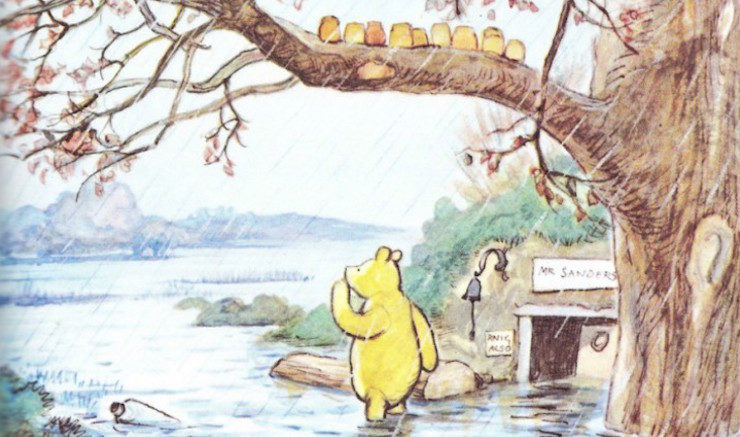

At least initially, however, fantasy did not pay the bills, and Milne focused mostly on plays, with the occasional novel, until he began publishing the Pooh stories in Punch in 1925. By 1926, he had enough stories for a small collection, simply entitled Winnie-the-Pooh. The second collection, The House at Pooh Corner, appeared in 1928. Both were illustrated by Ernest Shepard, then a cartoonist for Punch, who headed to the areas around Milne’s home to get an accurate sense of what the Hundred Acre Wood really looked like. Pooh also featured in some of the poems collected in Milne’s two collections of children’s poetry, When We Were Very Young and Now We Are Six.

All four books were instant hits, and Milne, whose agent had at first understandably argued with him about the wisdom of publishing collections of nursery rhymes and stories about his son’s teddy bear, found himself facing a completely different problem: the only thing anyone wanted from him was more stories about teddy bears. He refused, and—in a decision numerous lawyers were to benefit from later—sold the merchandising and most licensing rights to American literary agent and producer Stephen Slesinger, so that, later legend claimed, he would not have to deal with them.

Regardless of the reason, Slesinger’s marketing savvy helped make the already popular books even more popular. (As we’ll see, he was later to do the same for the Tarzan novels.) The public, adults and children alike, continued to clamor for more of Winnie-the-Pooh. Milne stuck stubbornly to plays, novels, and various nonfiction works.

It’s easy to see why the bear was more popular: once past the coy, slightly awkward introduction, Winnie-the-Pooh, is, as one of its characters might say, Very Good Indeed. Oh, certainly, a few matters need to be glossed over—for instance, just where does Pooh get all that honey (nine full jars in one story, which he easily consumes in just a few days)—and how does he pay for it? Why is Rabbit the only one of the characters to have an entire secondary set of friends and relations? Oh, sure, Owl mentions a relative or two, but we never see them, and I’m not entirely sure they exist. It’s certainly impressive that Owl can spell Tuesday—well, almost—but wouldn’t it be even more impressive if he could spell Wednesday—well, almost? And speaking of spelling, why can Piglet—not, we are assured, the most educated or clever of the characters in the woods—write a note begging for rescue when everyone else, including Christopher Robin, frequently struggles with basic spelling?

That said, it almost seems, well, heretical to say anything negative about a book that also has Pooh, the Bear with Very Little Brain; cowardly little Piglet who could be brave sometimes, and is secretly delighted to have people notice this; Owl, who can sorta spell things; busy, intelligent Rabbit; kindly Kanga and eager Roo; thoroughly depressed Eeyore, and Christopher Robin, who functions partly as a deux ex machina, able to solve nearly every problem except the true conundrum of finding the North Pole (and who, really, can blame him for that?) all engaging in thoroughly silly adventures.

When I was a kid, my favorite stories in Winnie-the-Pooh, by far, were the ones at the end of the book: the story where everyone heads off to find the North Pole—somewhat tricky, because no one, not even Rabbit nor Christopher Robin, knows exactly what the North Pole looks like; the story where Piglet is trapped in his house by rising floods, rescued by Christopher Robin and Pooh floating to him in an umbrella; and the final story, a party where Pooh—the one character in the books unable to read or write, is rewarded with a set of pencils at the end of a party in his honor.

Reading it now, I’m more struck by the opening chapters, and how subtly, almost cautiously, A.A. Milne draws us into the world of Winnie-the-Pooh. The first story is addressed to “you,” a character identified with the young Christopher Robin, who interacts with the tale both as Christopher Robin, a young boy listening to the story while clutching his teddy bear, and as Christopher Robin, a young boy helping his teddy bear trick some bees with some mud and a balloon—and eventually shooting the balloon and the bear down from the sky.

In the next story, the narrative continues to address Winnie-the-Pooh as “Bear.” But slowly, as Pooh becomes more and more of a character in his own right, surrounded by other characters in the forest, “Bear” disappears, replaced by “Pooh,” as if to emphasize that this is no longer the story of a child’s teddy bear, but rather the story of a very real Bear With Little Brain called Pooh. The framing story reappears at the end of Chapter Six, a story that, to the distress of the listening Christopher Robin, does not include Christopher Robin. The narrator hastily, if a little awkwardly, adds the boy to the story, with some prompting by Christopher Robin—until the listening Christopher Robin claims to remember the entire tale, and what he did in it.

The narrative device is then dropped again until the very end of the book, reminding us that these are, after all, just stories told to Christopher Robin and a teddy bear that he drags upstairs, bump bump bump, partly because—as Christopher Robin assures us—Pooh wants to hear all of the stories. Pooh may be just a touch vain, is all we are saying.

The House at Pooh Corner drops this narrative conceit almost entirely, one reason, perhaps, that I liked it more: in this book,Pooh is no longer just a teddy bear, but a very real bear. It opens not with an Introduction, but a Contradiction, an acknowledgement that almost all of the characters (except Tigger) had already been introduced and as a warning to hopeful small readers that Milne was not planning to churn out more Winnie the Pooh stories.

A distressing announcement, since The House at Pooh Corner is, if possible, better than the first book. By this time, Milne had full confidence in his characters and the world they inhabited, and it shows in the hilarious, often snappy dialogue. Eeyore, in particular, developed into a great comic character, able to say stuff like this:

“….So what it all comes to is that I built myself a house down by my little wood.”

“Did you really? How exciting!”

“The really exciting part,” said Eeyore in his most melancholy voice, “is that when I left it this morning it was there, and when I came back it wasn’t. Not at all, very natural, and it was only Eeyore’s house. But still I just wondered.”

Later, Eeyore developed a combination of superiority, kindness, and doom casting that made him one of the greatest, if not the greatest, character in the book. But Eeyore’s not the only source of hilarity: the book also has Pooh’s poems, Eeyore taking a sensible look at things, Tigger, Eeyore falling into a stream, Pooh explaining that lying face down on the floor is not the best way of looking at ceilings, and, if I haven’t mentioned him yet, Eeyore.

Also wise moments like this:

“Rabbit’s clever,” said Pooh thoughtfully.

“Yes,” said Piglet, “Rabbit’s clever.”

“And he has Brain.”

“Yes,” said Piglet, “Rabbit has Brain.”

There was a long silence.

“I suppose,” said Pooh, “that that’s why he never understands anything.”

Not coincidentally, in nearly every story, it’s Pooh and Piglet, not Rabbit and Owl, who save the day.

For all the humor, however, The House at Pooh Corner has more than a touch of melancholy. Things change. Owl’s house gets blown over by the wind—Kanga is horrified by its contents. Eeyore finds a new house for Owl, with only one slight problem—Piglet is already in it. In order to be nice and kind, Piglet has to move. Fortunately he can move in with Pooh.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

And above all, Christopher Robin is growing up. In a middle chapter, he promises to be back soon. That’s true, but in a later chapter, he is leaving—even if somewhere in a forest, a little boy and his bear will always be playing. It’s a firm end; as Milne had stated in the beginning, he was saying good-bye to his characters.

And the right end, since above all, the Pooh books are about friendship. Pooh realizes that he’s only really happy when he’s with Piglet or Christopher Robin. Both attempts to get newly arrived strangers to leave—Kanga and Roo in the first book, Tigger in the second—lead to near disaster for the participants. Piglet has to—let’s all gasp together now—have a bath, and Rabbit finds himself lost in the fog, grateful to be found by a bouncing Tigger. It’s an argument for pacifism and tolerance, but also a celebration of friendship. They may have started as toys. They’ve since become playmates and friends. And that, I think, along with the wit and charm, is one reason why the books became such an incredible success.

The other reason: the charming illustrations by illustrator Ernest Shepherd. His ghost would firmly disagree with me on this point, but the Pooh illustrations are among Shepherd’s best work, managing to convey Piglet’s terror, Eeyore’s depression, and Winnie-the-Pooh’s general cluelessness. Shepherd visited Ashdown Forest, where the stories are set, for additional inspiration; that touch of realism helped make the stories about talking stuffed animals seem, well, real.

Not everyone rejoiced in Winnie-the-Pooh’s success. A.A. Milne later considered the Pooh books a personal disaster, no matter how successful: they distracted public attention away from his adult novels and plays. Illustrator Ernest Shepherd glumly agreed about the effect of Pooh’s popularity on his own cartoons and illustrations: no one was interested. The real Christopher Robin Milne, always closer to his nanny than his parents, found himself saddled with a connection to Pooh for the rest of his life, and a difficult relationship with a father who by all accounts was not at all good with children in general and his son in particular. He later described his relationship with the Pooh books to an interviewer at the Telegraph as “something of a love-hate relationship,” while admitting that he was “quite fond of them really.” Later in life, he enjoyed a successful, happy life as a bookseller, but was never able to fully reconcile with either of his parents.

Over in the United States, Walt Disney knew little about the real Christopher Robin’s problems, and cared less. What he did see was two phenomenally popular books filled with talking animals (a Disney thing!) and humor (also a Disney thing!) This, he thought, would make a great cartoon.

This article was originally published in August 2015 as part of a series on rereading the source material for Disney Classics along with the films.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.